On more than one occasion, friends visiting or living in the UK from elsewhere have asked one of two (or, both) questions:

why do so few people in British cities live in apartments?

and:

why do British apartment blocks look so dystopian?

The first question is answered by the second, but when asked I struggled to give a meaningful explanation. This led me to investigate why exactly have architects and planners in Britain failed to provide comfortable, pleasant, and practical solutions to city living.

In the UK, there seems to be a real aversion to dense city living which leads to even relatively inner-city areas consisting of individual semi-detached and terraced houses, often with private gardens. In London, for example, by the outer fringes of Zone 2 (for context, the common reference point for Londoners is the London transport system, where concentric circles form six zones with Zone 1 being the centre) the streets already start to take on a suburban-esque feel. This spatial layout is normally reserved for commuter towns and outer suburbs in other European cities, not inner areas still within reasonable walkable distance to the centres of power.

In smaller British cities, the suburbanification happens much sooner. The only notable exception is perhaps Edinburgh, which is arguably the most European of British cities in terms of spatial patterns and social organisation. Very few British cities are organised in the doughnut-shape so ubiquitous (probably to the point of being near-universal) in major cities at least in Europe: the richest and nicest flats are in the city centre and are distinctly the preserve of the bourgeoisie, and the further you get from the dead centre (and presumably then, the cheaper the land becomes), the housing solutions become increasingly shabby. Only by the time you get to the outermost zones, or banlieues (hello Paris!), often you start to hit the problems that inner-city areas in the UK face.

In the UK (the pattern of which the US seems to follow), more often than not the trend is reversed. The outer areas are often where the bourgeoise lurk in their private houses with their own gardens, big driveways, seclusion, and cleaner air away from the dirt and the dangers of the inner city. Inner city areas tend to be either largely uninhabited (as in my city), full of empty properties that must be amassing capital for somebody, somewhere, or full of dystopian-looking council estates. Nowadays, the inner-city area in most provincial British cities has been used to house students in purpose-built new build (cheaply constructed, expensive to rent but student loans cover that off) after a speculative building boom and studentification in the last decade or so that brings with it its own problems.

Edinburgh Old Town, though, is full of attractive city-centre tenements that house the well-to-do. Meanwhile, the outskirts of Edinburgh are unlikely to attract the hordes that come to the UNESCO World Heritage City from all around the world each year: Cannot see them wanting to hang out in Niddrie for example, and neither Craigmillar nor Oxgangs.

Spatially speaking, then, the vast majority of cities in the UK are already radically different from mainland European counterparts. The reasons for this probably deserve a separate analysis of their own and derive from a complex set of historical factors related to our industrial and economic heritage, political organisation, and socio-cultural norms.

Spatial factors notwithstanding, this still does not answer the question as to why our tower blocks are so uninviting.

Tower Block: Modern Public Housing in England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

Tower block: Modern Public Housing in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Glendinning & Muthesius, 1994

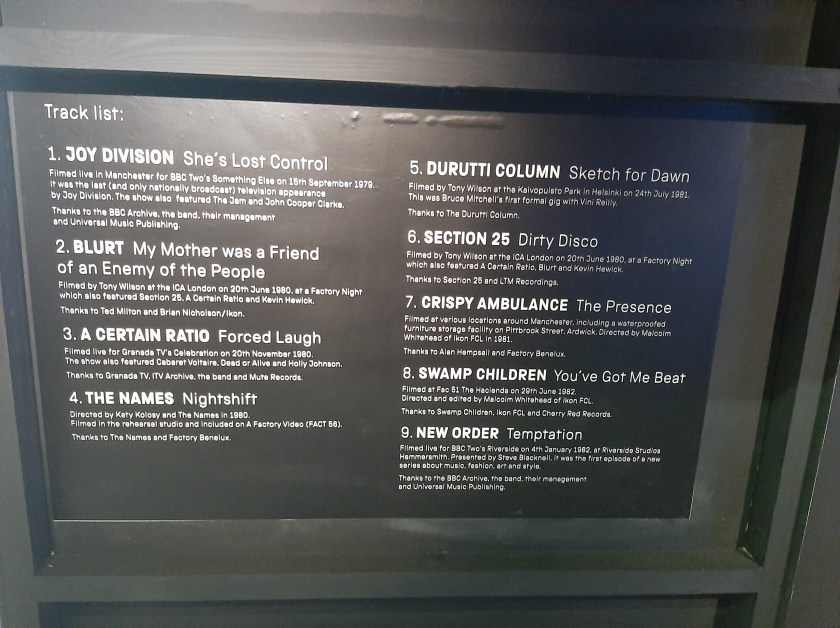

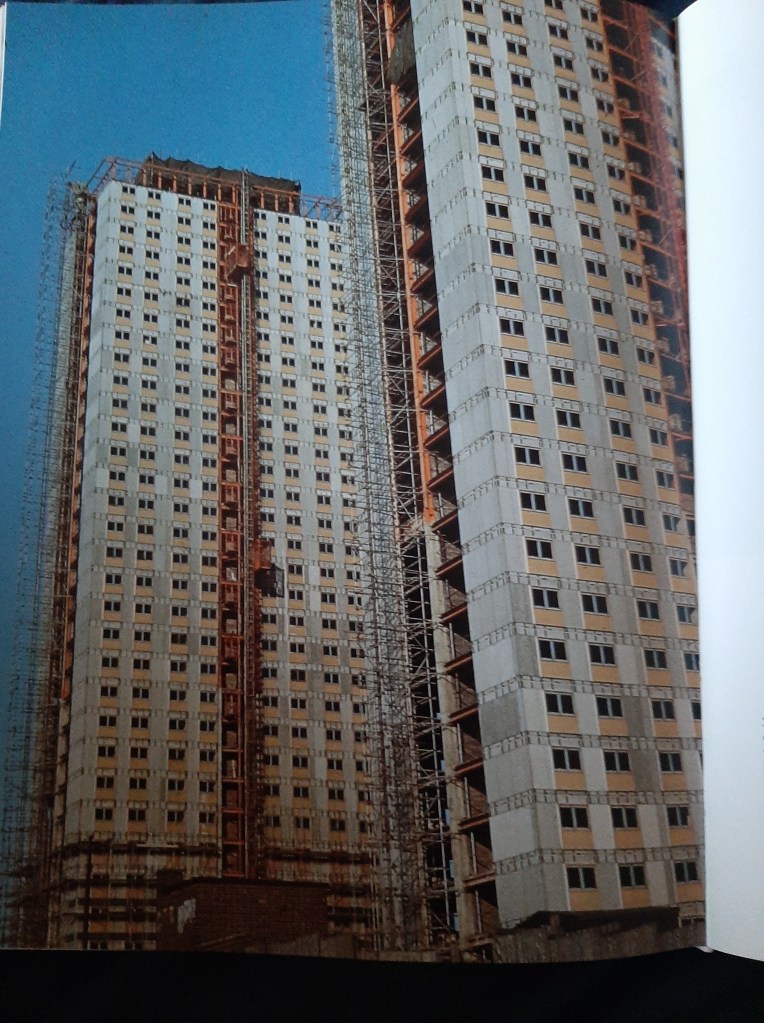

To delve deeper into the question, I picked up the dense and richly illustrated compendium of the history of post-war public housing in the four nations that constitute the UK. Miles Glendinning and Muthesius, academics and architectural historians anchored at the University of Edinburgh produced this detailed guide in 1994 covering technical design, policy factors (each nation has its own political traditions, cultural norms and social specificities leading to slight-to-moderate variations in national policies), and history.

The key conclusion from the book is that the post-war modern public housing building project in the UK was an impressive project, with the building boom starting in the 1950s, peaking in the 1960s (famously, the Conservative Minister for Housing in 1963 laid out a 10-year plan for mass council house building in the UK, absolutely unthinkable in today’s imaginary) and tapering off in the 1970s before Thatcher came to power and began her radical assault on the state (this is covered in more detail in my entry on Municipal Dreams: The Rise and Fall of Council Housing by John Boughton). However, what started off as a grand national project to adequately house the population after the Second World War soon descended into the murky world of local politics, private interest, and sheer profiteering.

The speed with which the housing boom took hold led to inferior quality control, which Adam Curtis’ 1984 documentary Inquiry: The Great British Housing Disaster shines a light on in a series of interviews with major actors in the housing boom such as Cleeve Barr and Tom Akroyd. Tower blocks in the UK have also suffered from a poor reputation in terms of safety: The Ronan Point disaster where a 22-storey block collapsed in Canning Town, East London in 1968 only 2 months after it opened, killing four people, and injuring 17 in a gas explosion. This was due to poor construction and faulty design and led to the removal of gas from high-rise buildings. As Curtis illustrates, however, this actually made things worse: rising costs of energy required to fuel the new electrical appliances fitted in council homes in the wake of Ronan Point led to people using their own makeshift solutions using gas cannisters, which obviously posed a significant danger to people living in the blocks. More recently, the fire in Lakanal House in Southwark, South London in 2009 led to six deaths and upwards of 20 injured. The cause was officially down to a faulty television set, but the exterior cladding in the tower block caught fire and spread rapidly through a dozen flats, trapping residents in their buildings. The only escape route, a central stairwell, filled with smoke making it difficult for people to escape.

Most recently, the Grenfell Tower tragedy in June 2017 killed seventy-two people and its charred remains are still there today, a mass tombstone on the West London skyline. The exterior cladding went up in flames in a matter of minutes, and the enquiry is still ongoing. Nothing has been officially confirmed as yet, but the role of government in securing procurement of this type of cladding for tower blocks across the country is the question that must be answered.

Understandably, since these disasters people in the UK have low confidence in the safety of tower blocks and this has not exactly contributed to a positive view of tower blocks. However, safety concerns are just one factor in determining why the UK has so badly executed a move to dense city living. Following comparisons with cities elsewhere in the world, and a closer look at the Tower Block project in the UK, here is what I think are the main contributing factors:

1. “An Englishman’s home is his castle”: Cultural preferences for private over public

The notion of collective and the suspicion with which anything of public value is treated in this country runs unbelievably deep. There is such a deeply held belief that public space is something to be avoided and that sharing with others is bad that I am sure paved the way to an easy roll-over into the shitty mass privatisation of public goods and the death knell of “gas and water” socialism in the Thatcher years.

We credit Thatcher with too much and she is an easy target; scratching more deeply under the surface of this wretched country and it seems that many of Thatcher’s beliefs were already alive and well. She was successful at capturing them and leaning into them, I suppose.

But that is the most depressing thing: I am increasingly finding all the things I despise about this country run millennia deep. I cannot see the way to a better and fairer future. Only the opposite – I see the signs of increased gaping inequality in a country that’s already far more unequal than most of the usual European comparators (with which we are increasingly lagging behind on pretty much all social and economic counts to the point that I’m not so sure we can treat Germany, Netherlands, France etc as a comparator anymore).

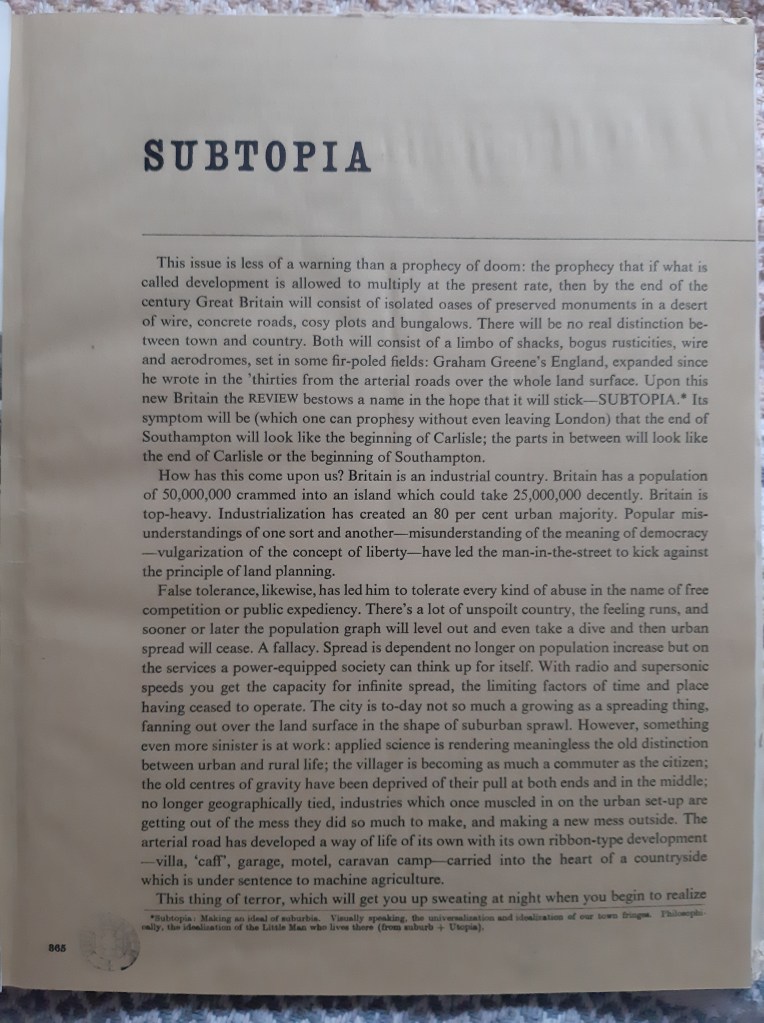

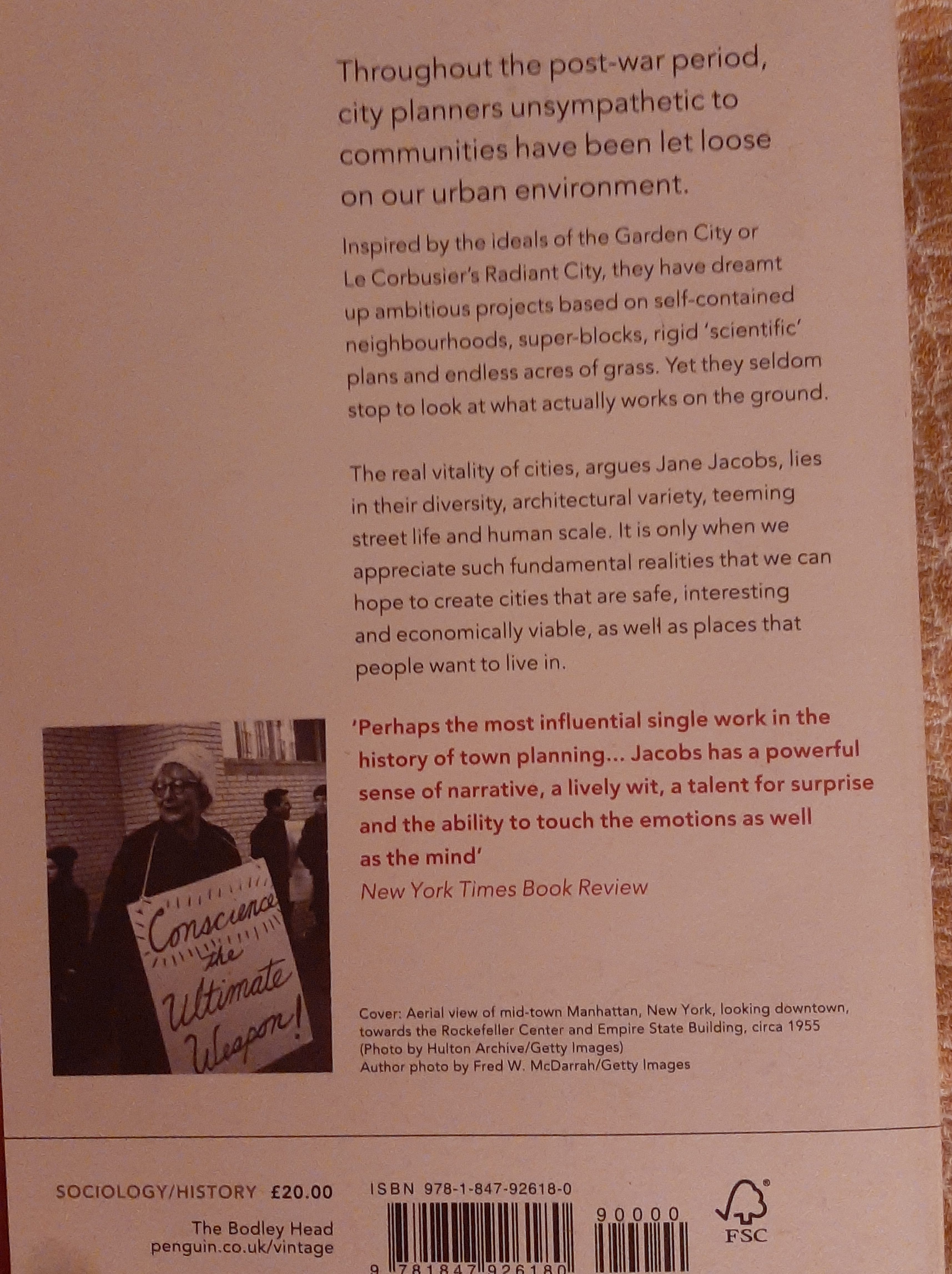

But I digress. Ruth Glass wrote in the 1960s in her collection of essays “Cliches of Urban Doom” about the Merrie England dream – the pervasive desire to live in a pastoral, all-English, quaint village community replete with thatched roof houses and a village green.

This is, of course, not a realistic depiction of 21st or even 20th century Britain, but it seems to stick in the national imaginary. The ideal is to live in a cottage of one’s own, where you can shut the front door, lock the garden gate, and keep the prying eyes of neighbours at bay. Living in an apartment, nose-to-nose with neighbours above, below, opposite, and to each side is obviously not in line with that dream. It would be far to difficult to avoid other people. Conversely, though, I introduced my Italian partner to the concept of “curtain twitching,” which to me is even more quintessentially British than the Merrie England ideal described above.

He laughed and pointed out that it is highly strange that in a country so obsessed with privacy people are damn nosy and status obsessed. He noted that in Italy, people are used to living cheek-by-jowl with neighbours, but nobody really gives two hoots about what anyone else is up to. I suppose, keeping everything in the open means that there is nothing really to hide. In contrast, British homes, with their tall hedges, front gardens and thick curtains are shrouded in mystery.

Garden City Movement of Ebenezer Howard, is a work in utopian thinking draws from the Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin’s thinking. Howard is keen to emphasis his not socialist but not “individualist” slant – a true Fabian in the making (something I have strong opinons about but that’s for another time) – or a third way / mixed economy supporter before his time. From this standpoint he supports keeping workers apart against threat of Bolshevism. More on that later.

In 2013, Daily Mail ran an article called “Bring Back Bungalows.” A general rule I follow in life is that if the Daily Mail endorses it then “it” must be wrong. And if anything would be a mouthpiece for the Merrie England ideal, it would be the Daily Mail. I think that confirms that the paranoia of letting city-dwellers live close together might lead to revolution is still, over a century after the Bolsheviks, a subconscious preoccupation of the England ruling class.

2. Poor planning

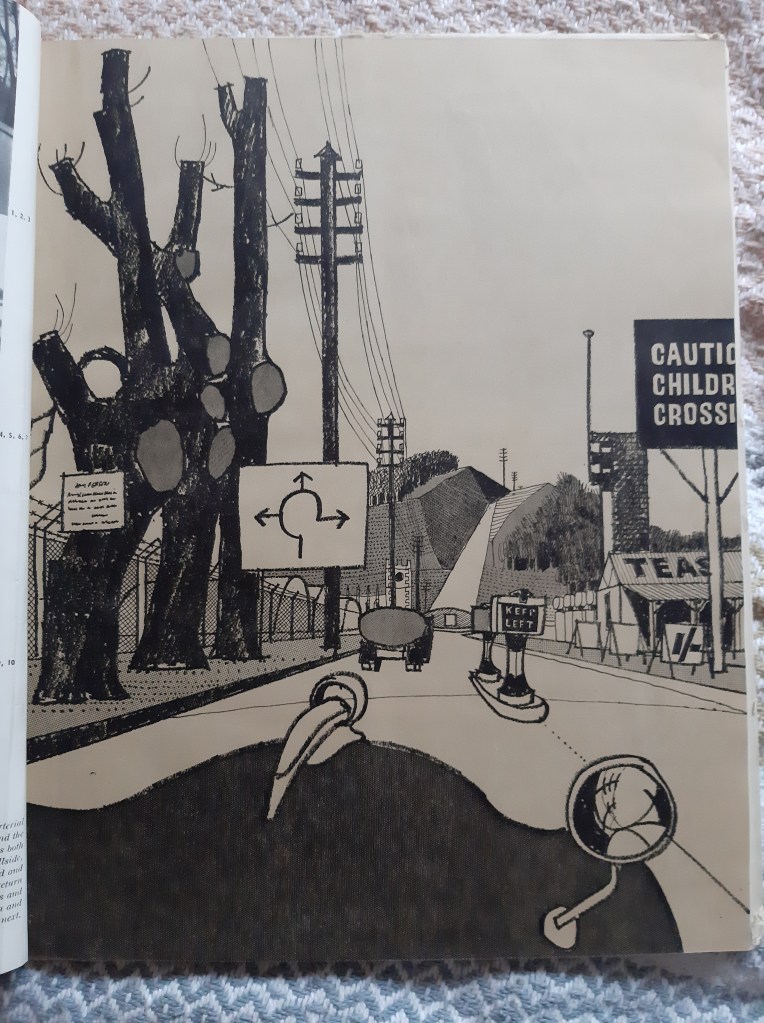

In many UK cities, the usual skyline is overwhelming low-rise interrupted only by standalone 15-storey plus tower blocks dotted at random. This has quite a jarring effect, and the tower blocks stand out like a sore thumb.

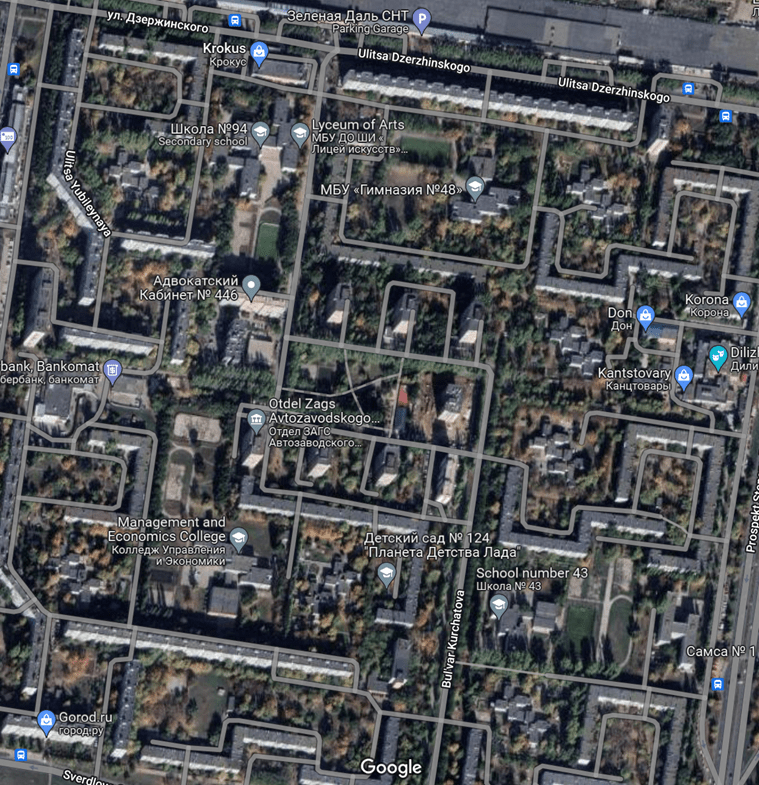

From a spatial point of view, this is the result of a combination of land use policies and practical considerations related to the quality of the land. In Tower Blocks, Glendinning and Muthesius highlight the large degree of autonomy local councils enjoyed in planning and building in the 1960s. While the national guidelines encouraged an increased densification, likely conceived with London in the forefront of their minds, some councils such as Leeds and Newcastle preferred to expand their urban core. In clearing out the riverside slums around the riverside in Newcastle, for example, the council under T. Dan Smith’s guide developed land further out from the city, particularly around former industrial sites in the East and West of the city.

This led to the construction of tower blocks on cleared brownfield sites, previously used for mining. As such, the structural property of the land is rather poor. Much of the land in the North East mining country, for example, is like Swiss cheese. I live right next to one of these T. Dan Smith’s tower blocks and looking out of my living room window I can see that each house is my street is at a slightly different level, creating a somewhat Tim Burton-esque vibe. Subsidence is a way of life here. At the end of the street a 20-storey tower block looms over us, on a former mine shaft. The tower blocks were built on any spot that was deemed sufficiently structurally sounds, which leads to a sporadic landscape.

These one-off tower blocks look quite different to the rows of squat tower blocks that tend to be grouped together, among more medium-sized (4-6 storey) buildings in other European cities. This gives a more gradual skyline, as opposed to the contrasting scale of a single 20-storey block erupting from a sea of 2-storey homes.

3. Political stigmatism and the collective imaginary

The lack of continuity between the tower blocks and their surrounding areas did create fertile conditions for those up to no good to thrive. Rather than landscaping the areas around the tower blocks, the 1950s-1970s tower blocks are usually surrounded by concrete. In addition, many of the visionary architects of the time had these ideas of “playful” passages, walkways in the sky, nooks, and crannies for people to walk around (all concrete, of course), and concrete common areas to sit outside. I’m sure these were designed with the aim of creating a pleasant environment for tower block dwellers, who had no access to their own outside space, but the effect is really quite the opposite.

Instead of vibrant, lively places they became convenient locations for dodgy dealings, with their hidden corners and networks of alleyways, underpasses, and passages.

The situation was made so much worse by Thatcher’s assault on the social housing sector and mass sell-off of council blocks, which led to a sort of social engineering and negative feedback loop. Oscar Newman’s defensible space theory also had a disproportionate and unfounded influence on housing theory in the UK from the 1970s onwards. Newman’s theory, focused on the now-demolished Prutt-Igoe housing project in St. Louis, Missouri, posits that the more private a space is, the more control and influence the resident has over it. He notes that where space is collective, since it belongs to no specific individual then it is likely to attract criminal behaviour. This completely flies in the face of the Greek and Roman architectural theories that prized common space (Agora and the Forum, really the forerunner in some respects of the post-renaissance Italian piazza) and the opportunity for city dwellers to intermingle in neutral territory. Defensible space draws on the most Anglo-centric phobia of the collective, which is seen as suspicious and dangerous as people simply cannot be trusted to look after what is not directly theirs.

Following this, housing in the Anglo world aims to physically defend itself from outsiders and plays into fear of the unknown. Even today, the Secured by Design in the UK is a police initiative that aims to improve the security of buildings by fitting them with surveillance devices such as CCTV systems and bars over windows. This has led to some highly unwelcoming and quite frankly intimidating architecture. Anna Minton, author of Ground Control, described it as “oppressive,” and I certainly tend to agree.

4. Value engineering

Vitruvius, the Roman architect, and engineer who wrote De Architectura (the collection of ten books on architecture written in 1st century BC), notes in Book I that no expense should be spared on materials required for building, especially not public buildings. Fast forward a couple of millennia, and we see that for all the current government’s talk about one of the three Vitruvian principles, Venustas (beauty) even enshrining it in the latest raft of planning reforms (see Building Better, Building Beautiful bluuurk), they conveniently forgot the point old V repeatedly hammered home about not being cheap and skimping on quality.

This is not just our current government, of course, but cheapness and cost-saving (for the masses that is, of course profit for the few is the mantra of the day) took first place over utility quality, comfort, and even safety long ago. Glendinning and Muthesius’ Tower Block tome offers some insight into the world of value engineering, and why it leads to mediocre quality. Essentially, value engineering means that if a cheaper alternative is available to a solution, then the cheapest one must be procured.

Looking at how the Tower Blocks of the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s and even more so, the new builds of the 1990s and early 21st century one can really see value engineering at work. Certainly, the Venustas bit was lost here as well. Adam Curtis’ documentary, available on YouTube in its full glory, The Great British Housing Disaster, certainly gives an illustration of what cost cutting and shoddy workmanship leads to. And of course there were also tragic consequences, not only Grenfell (cheap cladding and surely corruption to an as-yet unknown quality in government procurement processes), but also Ronan Point, the tower block in East London that collapsed in 1968 a mere two months after it opened and also Lakanal House, again in London in 2009 which caught fire and it was shown that the fire escape routes were simply a long way short of sufficient.

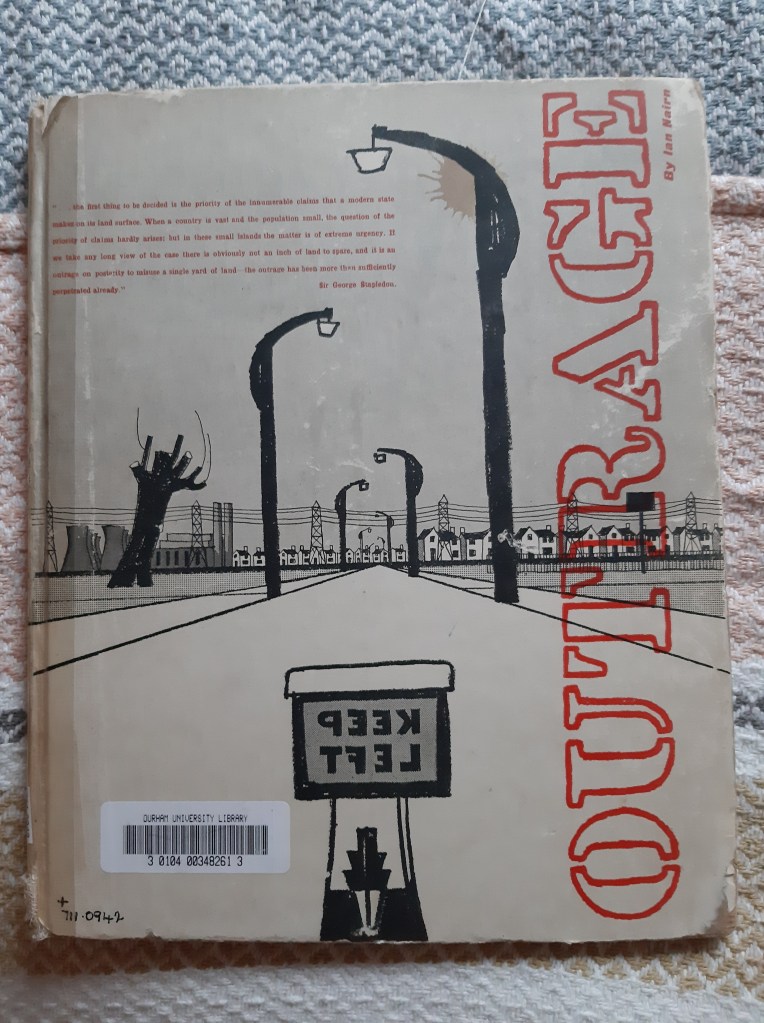

5. Anti-urbanism and prioritisation of fast and private mobility

The latter is not unique to the UK, of course, but the instinctively anti-urban sentiment seems to run deeper here than elsewhere (see point 1). The UK was last modernised really in the 1950s and 1960s, after much of the industrial cities were flattened during WWII. Reconstruction coincided with the rise of the private car, and our cities are certainly engineered in an extremely car-centric way. Coventry, which was heavily bombed, is perhaps the most shocking example of this I have seen. Busy arterial roads cut through inner city areas, making it exceedingly difficult to get around by foot.

A society heavily reliant on private mobility and where public transport has been heavily stigmatised and heavily cut back in recent decades, making it costly, disjointed, and inconvenient (Thatcher famously said that anyone on a bus over aged 25 is a failure), doesn’t lend itself well to housing that has little to no private car facilities, as many of the mid-century tower blocks do. Coupled with a cultural preference for private space and an own garden, individual houses preferably with a drive or a private garage attached are much desired. Car parking solutions are indeed a factor when people here seek to buy their own home.

6. Lack of private outdoor space

One thing that the UK severely misunderstands is the concept of the balcony. Where private homes and private gardens are secured, I suppose this has the impact of downgrading any other solutions of private space in more collective living arrangements. Tower blocks in the UK rarely have balconies available for residents’ use, and even new builds tend to use the misleadingly named “Juliet balconies” (aka bars over the windows to stop people jumping out, I think, I cannot see any other function they might serve). As a result, tower block living is deemed wholly undesirable as there is no individual access to outside space.

Balconies fulfil a much greater role in Italy, France, Spain, and other countries particularly in the South of Europe. This alone probably warrants a separate entry in its own right.

8. Scale

Scale in the UK is strange. Until recently, even London had a relatively low skyline compared to cities of a comparable size elsewhere in the world. Still today most provincial cities consist largely of low-rise buildings, punctuated discordantly by enormous tower blocks. Scale is important, and it is underrated. Too tall, and without the right frames of reference, then it is out of whack with surroundings and creates a hostile, dystopic atmosphere.

In the film the Human Scale, Jan Gehl outlines how scale can be achieved to balance the need for dense living with a comfortable and welcoming city-feel. Around eight storeys is the perfect dimension for the human brain, as long as the buildings are anchored to street-level somehow. This can be achieved by adding trees, or fitting ground floors with balconies or canopies covering shop fronts and cafes. It is something that the average Brit is eager to romanticise about large European cities, and indeed many mainland European cities do achieve the balance of dense and cosy. Here, with a suspicion of public space and no traditional street culture to speak of (beyond booze-fuelled mania, but that is a different story), it is something distinctly lacking in British cities.

Our low-rise cities coupled with inhumanly scaled buildings definitely contribute to a sterile and unforgiving street environment, even more marked in cities that have recently undergone a vertical building boom such as Manchester, London, and Birmingham. Rather than a sense of convivial street life, the overwhelming feeling is that of the ever-increasing blood-sucking grip of the financial sector is never far away.

9. Lack of maintenance

The individual flats inside the tower blocks (at least the ones I have seen) tend to be quite roomy on average, certainly bigger than the standard new builds aimed at working or middle-classes. Indeed, in the 1950s-1960s much thought was put into spatial standards and how much space residents would need to go about their day-to-day in their dwellings. Local council housing teams tended to employ sociologists who would make calculations based on family size, demographics, and various other factors and ended up with a generous square metreage by today’s standards. When families first moved into the new tower blocks from their cramped, overcrowded inner city terraces and slum areas, they were surely quite taken by the relatively high standard of dwelling they had newly acquired.

However, a cursory glance today shows that not much in the way of modernisation has really taken place since the 1960s. Lift shafts are often in a poor state, interior décor has barely been touched apart from perhaps a new lick of paint every now and again, and broken windows, intercom systems, and doors seem to be a relatively standard feature of the old tower blocks.

Surely if maintenance cycles had been rolled out on the regular and the flats were modernised incrementally and equipped with modern technology as it evolved, they’d be much better places to live. But no, most of them still seem to be stuck in the 1960s and after more than half a century of wear and tear that hardly leads to a desirable place to live.

10. … Perhaps they are back in vogue?

That said, apartment living – as opposed to living in a “block of flats,” carefully distinguished by property developer marketing-speak, seems to be making a comeback. Luxury apartments (a far cry in aesthetic from the classic “block of flats” but I would argue that quality of the new ones has been severely compromised comparing like-for-like) are cropping up in waterfront areas and former industrial districts across this highly financialised country, largely populated by young, middle-class professionals. This is borne partially out of necessity but also logic of the market, which in this country certainly leaves no stone unturned when it comes to opportunities to extract profit. That, however, is an entry for another day.